We made a corn whiskey mash recently and documented the process for others to see. Though, before we get started, a reminder: making mash is legal. It' just like making beer, which is legal in 48 states in the US. However, distilling alcohol is illegal without a federal fuel alcohol or distilled spirit plant permit as well as relevant state and local permits. Our distillation equipment is designed for legal uses only and the information in this article is for educational purposes only. Please read our complete legal summary for more information on the legalities of distillation.

The following is a detailed corn mash recipe, illustrated with pictures. This is one of our older recipes, so this is a tried and true process. For a newer version of this recipe check out our article on How to Make Moonshine.

When we tested this procedure, we had a fuel alcohol permit and we were in compliance with state and federal regulations. We produced, stored, and used this alcohol in accordance with TTB requirements. We also kept and reported production logs in accordance with TTB fuel alcohol permit requirements.

The following is how a commercial distillery would likely make corn whiskey

Mashing Equipment

-

First, making corn whiskey mash is pretty simple. Less equipment could be used, but having the following basic equipment will make this a lot easier. All a distiller needs is a large pot for mashing, a wort chiller for cooling liquid, a brewers thermometer, cheesecloth, a plastic funnel, and a spare plastic bucket for aeration. Make sure to check out our recommended distillation equipment guide.

Corn Mash Ingredients

- As far as ingredients go, a distiller needs the following:

- 8.5 lbs. of crushed corn (sometimes called flaked maize)

- 2 lbs. of crushed malted barley*

- 6.5 gallons of water

- 1 package of bread yeast (Fleischmann's Active Dry works well)

*Note, barley MUST be malted, otherwise recipe will not work (more on this below).

How To Make Corn Mash

-

We heated 6.5 gallons of water to roughly 165 degrees Fahrenheit. Once the temperature was reached, we cut off the heat. It won't be needed for a while. Next, we poured all of the crushed corn into the water and stirred for 3-5 minutes. After that we stirred for 5-10 seconds every 5 minutes. This is the start of our mash.

-

The corn will turn to a "gel" as it gets stirred up. We weren't alarmed when this happened as this is perfectly normal. The corn is being broken down and starch is being released, which makes the mixture quite thick. Once the barley is added and mashing begins, the mixture will thin out considerably.

-

We monitored the temperature as we stirred. Once the temperature dropped to 152 degrees, we added the malted barley and stirred for 1-2 minutes. Once stirred, we covered and let the mixture "rest" (sit) for 90 minutes.

-

During the rest, enzymes in the malted barley will convert starches in the corn and the barley into sugar. Later, during the fermentation process, yeast will be added and the yeast will actually turn the sugar into alcohol. So, to rephrase that, what we're ultimately trying to do during mashing is turn grain starch into sugar so we can add yeast and turn the sugar into alcohol during the fermentation process. The enzymes found in malted grains (i.e. malted barley) are what convert the starches into sugar. Without enzymes, none of the starch will be converted into sugar and fermentation will fail. So, it is critically important to use malted barley, and not regular flaked barley, for this recipe.

-

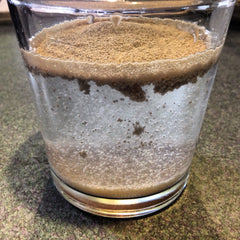

While the mash is resting, we made a "yeast starter" by re-hydrating our yeast in a glass of water. For this recipe, we added 2 packages of active dry bread yeast to 1/2 cup of 110 degrees F water along with 1 tsp. of sugar.

-

Completing this step allowed us to verify that the yeast is good (a "yeast cake" will form and expand on top of the water if it's working). This step also allows the yeast to get a "head start." Once added to the mash, the yeast will be able to begin rapid fermentation immediately. This reduces the chances of contamination of the mash by ambient bacteria.

-

After a 90 minute rest, we needed to cool the mash down to a temperature suitable for adding yeast. This is generally somewhere in the neighborhood of 70 degrees. To cool a mash, a distiller can either use an immersion chiller to rapidly cool the mash, or simply leave it sit for several hours. Once cool, we poured the mash through a cheesecloth (any fine strainer will do) to separate solids from the liquids.

-

It's always a good idea to cool the mash as quickly as possible to reduce the likelihood that the mash will become contaminated with ambient bacteria while it is sitting. Immersion chillers work great for this.

-

We like to use a cheesecloth to separate solids from liquids. We scoop a little bit into the cheesecloth bag at a time and then squeeze the hell out of it. Using small amounts allows us to wring out the bag and recover most of the liquid (which means we'll end up with more final product).

-

After cooling and removing grain solids, we aerated by pouring the mash back and forth between two sanitized buckets. We made sure to aerate aggressively enough to see froth and bubbles forming (that's a sign of good aeration). We poured the liquid back and forth 10-15 times. After aerating, we took a specific gravity reading by filling a test tube and using a hydrometer. Another way a distiller might do this is by dropping a bit onto a refractometer collection plate and taking a refractometer reading.

-

Aeration is critically important. Yeast need oxygen to survive. Without aeration fermentation could fail and the yeast won't do anything. Aerate!

-

The specific gravity reading is used to determine potential starting alcohol. Basically, it allows one to determine how much alcohol will be in the wash if everything goes well during fermentation. After fermentation, another reading will be taken to determine actual alcohol content of the wash. Both readings are needed to calculate this number.

-

After aerating and taking a specific gravity reading, we added the entire contents of our yeast starter to the mash. Finally, we transferred our mash to a fermentation vessel.

-

We use 2 small packages of bread yeast per 5 gallons of mash

-

Our favorite container for fermentation is a 6.5 gallon glass carboy.

-

The last step of the mashing process is fermentation. Once the mash was transferred to the fermenter, we sealed it with an airlock and left it sit for at least 1 week. A distiller could leave this sit for as many as 3 weeks. If it's still bubbling, it's still fermenting. We left it alone until we didn't see any bubbles.

-

We made our own airlock using a rubber stopper, some clear plastic hose, and some zip ties. We looped the hose a few times and added some sanitizer solution so the very bottom of a few of the loops are full, forcing air to bubble out while not letting any air in.

Distillation

For a quick tutorial on how a commercial distiller would turn a wash into high proof alcohol, check out How to Distill - 101. Also, make sure to check out our copper still kits before leaving.

Leave a comment